| Home |

| Gaynor |

| Mike |

| Art |

| Theatre |

| Book Shop |

New Globe PlayhouseA Living Theatre1997 Season |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Introduction |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

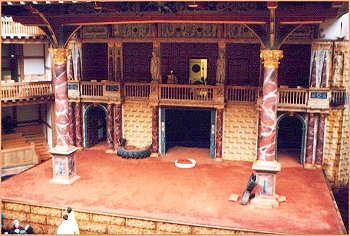

| The reconstructed Globe Playhouse on London's Bankside opened its gates for the first time in May 1997, and was officially opened by the Queen in mid June. It is as accurate a reproduction of the first Globe as could be done given the knowledge we have, but as a member of the audience twice now, I can testify that this is not a museum piece for the instruction of scholars, but a very exciting living theatre. The first season included two Shakespeare plays The life of Henry the Fift and The Winter's Tale. There were also two plays by contemporaries of Shakespeare, but I'm afraid I didn't manage to see those. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Henry V |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

On June 6th I attended an afternoon performance of The life of Henry the Fift (No that's not a typo, it really is Fift), directed by Richard Olivier and featuring the Artistic Director of the Globe, Mark Rylance as Prince Hal. The company had decided to make the production as authentic as possible, and like Shakespeare's company did not include any women in the cast. Female characters were played by young men or boys. The actors were entirely dressed in recreated clothing of the period. "No Calvin Klein underwear here" said the designer Jenny Tiramani. The stage was covered in a layer of rushes. There was no scenery. While most playgoers found their seats, and the "groundlings" wandered into the yard to stand around the stage, a persistent drum beat emanated from the stage gallery. Soon the entire cast trouped on to the stage, each banging a staff on the ground in time to the drum beat, and then suddenly stopped. O for a muse of fire, that would ascend started Mark Rylance as chorus. No museum piece staging this, but an exciting, warlike start to an exciting, warlike play. It all worked together brilliantly. Rylance's Hal was a hesitant, uncertain man, but a stirring, ruthless prince. His Crispin's Day speech, addressed partly to the groundlings, roused the playgoers to cheering patriotism, even though a great many were American! In his love scene with Katherine, played by the excellent Toby Cockerell, Rylance was nervous and touching. And what of the other star of the day, the Wooden O, the great Globe itself? It was a triumph! The communication between the players and the playgoers was real. Whenever the actors addressed the audience directly they responded with enthusiasm. The lack of scenery was never a problem. The Bard wrote for this setting, and told us where we are supposed to be in every scene either directly or indirectly. More intriguing was the sense that on occasion the scene was changing before our eyes. Henry talks to some lords, they leave the stage and are replaced by other characters, and Hal addresses them, but I felt that time had moved on and we were in another part of the battlefield. This is screenplay writing! Only the imposition of fixed scenery after Shakespeare's era made us expect plays to be enacted in 'real time'. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Winter's Tale |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

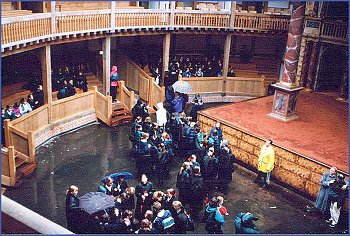

| I took the photographs on this page during my second visit to the New Globe in the summer of 1997. The play was

The Winter's Tale and the weather was not kind. At this mid-week performance the "groundlings"

consisting mainly of schoolgirls were given seats under cover after the first interval. This production directed by David Freeman was quite different to Henry. The stage was covered with a layer of sand, the costumes were of no particular era, and seats, thrones etc. were made from tractor tyres. "Elizabethan tractors, I presume!" quipped a woman in front of me. I felt that the production could have been staged anywhere. It didn't use the strengths of the Globe, and frankly did not illuminate this difficult play for me. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Internal |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home|Gaynor|Mike|Art|Theatre|Book Shop |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Updated 13th January 2001 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||